Cycling esports coach Alex Coh weighs in on the Elite vs. World Tour debate and the training philosophy that propels his athletes onto the podium.

By Australian Cycling Esports National Champion Kate Trdin

My recent piece “Deciphering How Indoor Specialists Can Push World Tour Power” seemed to strike a chord, for better or worse. Frankly, I was pleasantly surprised with its overwhelmingly positive reception, although a few critics did seem to miss the point.

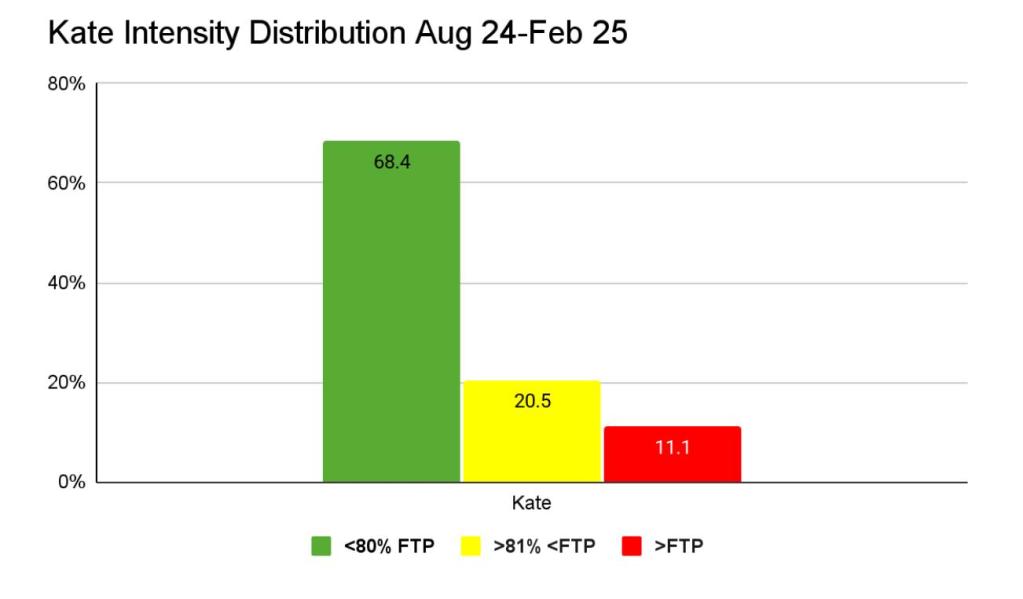

Although the article certainly generated some conversation, I couldn’t help but feel that it was in some way unfinished. You see, being an esports specialist myself, I am highly aware that my training is vastly different from what it would be if I were racing outdoors.

My training data shows that my power numbers have actually improved significantly since I started training as an indoor specialist, compared to when I was riding on the road. Reflecting on this, I realized that the way in which esports athletes train must also be considered, when appraising the outstanding power performances we are currently seeing.

The Physiology of Cycling Performance, in a Nutshell

While in reality there are a variety of physical and psychological elements that intersect to produce elite cycling performance, taking a reductionist approach, we can narrow performance down to a few key factors:

- Aerobic capacity (VO2 max) is essentially how much oxygen the body can use to produce energy, and is critical for efforts lasting 3-8 minutes.

- Lactate threshold is how well a rider can clear lactate from the bloodstream, which is essential to maintaining sustained power output, e.g., 20-40 mins.

- Endurance/fatigue resistance describes the ability to repeat efforts under fatigue and effectively switch between fuel sources—fat and carbohydrates.

- Neuromuscular efficiency is the ability to convert energy inside the muscles into power, and is mediated by the nervous system recruitment and coordination of muscles.

- Anaerobic capacity enables riders to produce short bursts of power needed for covering attacks or sprinting to the line.

Traditional Training Approaches

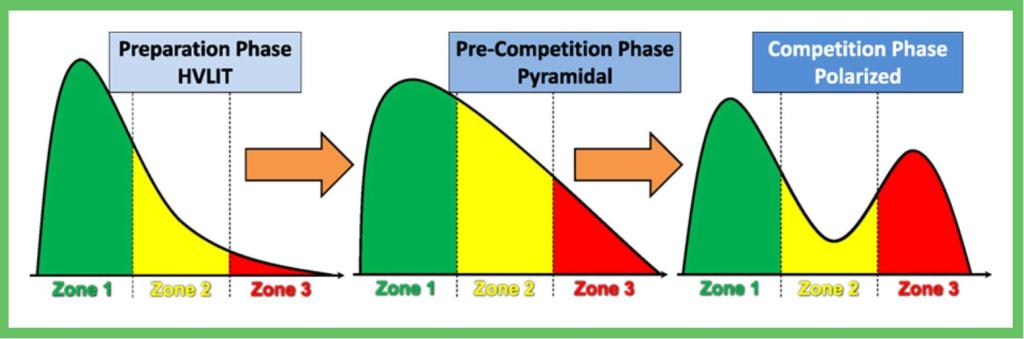

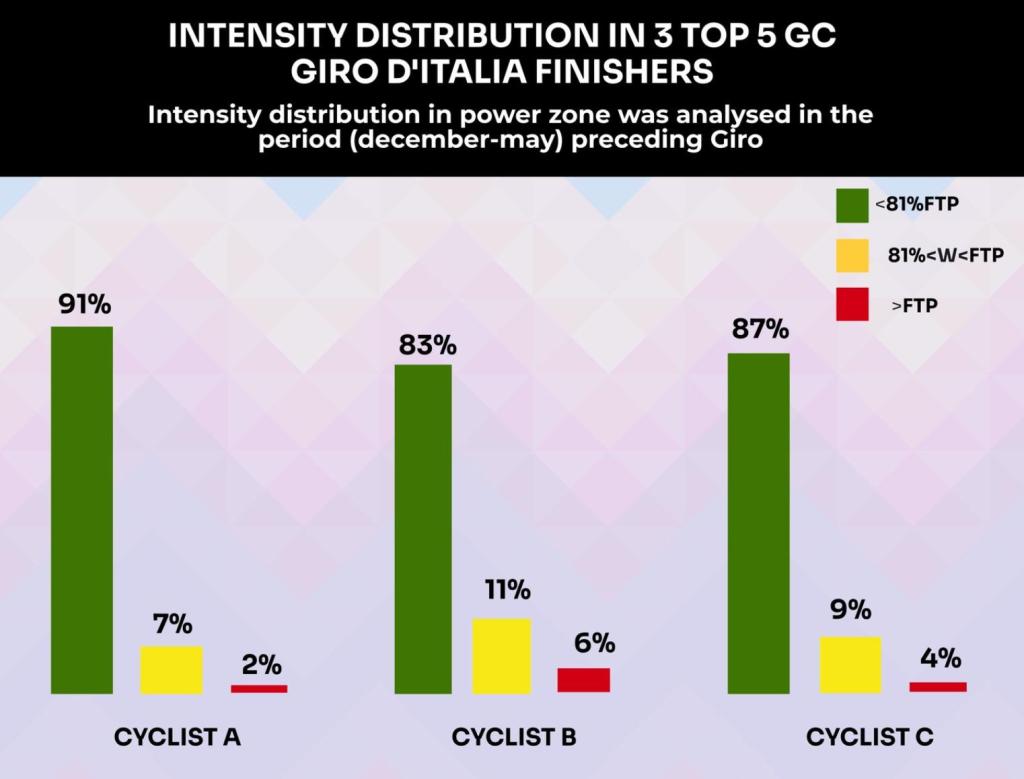

A polarized training approach is generally considered the gold standard training model for cycling and most other endurance sports (Rivera-Kofler et al., 2024). Traditionally, this involves completing 80% of training volume below LT1 (i.e., in zones 1 and 2), with the remaining 20% at LT2 or above (i.e., zones 4, 5, 6).

There are many variations within this approach, however, such as 90/10 or the pyramidal approach, which includes some moderate-intensity efforts between LT1 and LT2 (i.e., zone 3). The premise behind these approaches is the use of low-intensity training to build endurance (i.e., fatigue resistance), which is critical for races lasting longer than 2 hours, and to allow the body to recover and adapt from the hard workouts.

The remaining portion of intensity then builds the rider’s VO2 max, anaerobic, and lactate clearance capacities. This is also thought to be aided somewhat by maintaining a high volume of low intensity training, which increases mitochondrial density and cardiorespiratory adaptations (Seiler, S., & Kjerland, 2006).

What About the Unique Physiological Demands of Cycling Esports?

Being an endurance sport with comparable patterns of muscular recruitment and activation, the physiological demands of esports are similar to those of other endurance cycling disciplines. However, there are vital differences.

I have enlisted the expertise of Alex Coh, one of the few coaches widely known for his cycling esports-specific focus, to help me examine these in further detail.

As someone who coaches cyclists of various disciplines, Alex is the perfect man for the job. In fact, Alex’s coaching experience spans over two decades, during which he has coached amateurs, domestic/conti pros, and World Tour pros. He has an impressive client list of top-level esports racers.

If you’re considering cycling coaching of any kind, I highly recommend reaching out to Alex Coh Coaching. Full transparency—Alex is my coach, and his guidance has taken me to a level I never thought possible.

Alex, thank you so much for taking the time out of your undoubtedly crazy work schedule to chat. Can you tell us about your journey into coaching endurance sports and what inspired you to pursue this career path?

My journey into coaching began over 22 years ago as an endurance athlete. I faced challenges with standardized training plans and uninterested coaches that didn’t consider individual factors like available training time, recovery, fueling, or hydration.

ESPECIALLY FUELING AND HYDRATION. This led to overtraining and a six-month recovery period. Determined to find a better way, I immersed myself in learning about physiology, anatomy, training response measuring, and personalized coaching. I initially tested methods on myself and friends before formally starting coaching athletes five years ago.

Now that you have a well-established coaching business, roughly how much time per week do you spend coaching, and can you give us an overview of the different types of athletes you coach?

I dedicate a significant portion of my week to coaching, providing daily feedback on workouts and offering regular consultations. My clientele ranges from beginners to World Tour cyclists, encompassing various fitness levels in cycling and triathlon. I would say I work an average of 60 hours a week. (I can hear the cringe in the reader now.)

Honestly, it doesn’t feel like work most of the time, because I LOVE IT, and because I have worked so hard to have the ability to pick the people I coach and work with, which is why I love it haha. This is an acquired luxury most coaches do not have and mine came from initially working 100+ hours a week in the first year of the company formation.

You have developed quite a reputation within the esports scene as being one of the most well-renowned coaches offering esports-specific services. How did you identify the need for esports-specific coaching, and what drew you towards the esports cycling scene?

The rise of esports cycling presented unique challenges distinct from traditional road racing. Recognizing the specific physiological and strategic demands of virtual racing, I saw an opportunity to apply my coaching philosophy to this emerging discipline.

The ability to analyze precise data and tailor training to the unique aspects of esports racing drew me to this field, but more than that, the ability to eliminate travel, cost, risk associated with the outdoor scene entirely and race the world´s best from what is essentially your living room. No other top-level sport offers this.

When I started, there weren’t really that many people doing any kind of structure for esports, and in general, it was considered that you don’t really need a coach. Most still think this is the case despite all evidence pointing in the other direction.

All else aside, it is nearly impossible to be objective with your own training plan. You will always do or want to do more, which is why we ended up in endurance sports. It takes a specific personality for that.

As a fellow Peloton of Pain athlete, I see your programing as highly unique and probably quite different from what I would expect to be programmed for an elite road rider, aside from the somewhat expected reduction in overall training volume. What do you believe are the key physiological demands of esports racing, and in what ways does your training philosophy address these?

Due to the dynamic nature of virtual competitions, esports racing demands rapid power surges, sustained high-intensity efforts, and quick recovery. My training philosophy focuses on enhancing anaerobic capacity, improving neuromuscular efficiency and aerobic efficiency, and developing mental resilience.

Mental resilience actually in my mind comes before anything else, but to build it, you need to first build the physical one. There is a beautiful world on the other end of suffering. Someone smarter than me said that, and it stands true. Workouts are designed to simulate the specific intensity patterns of esports races, ensuring athletes are well-prepared for the unique challenges they present.

As someone who coaches both esports and road riders, in what key ways does your weekly programming differ for an elite esports athlete versus someone racing at an elite level on the road?

For elite esports athletes, the programming emphasizes high-intensity interval training with shorter recovery periods, reflecting the demands of virtual racing. We do not, however, underestimate the aerobic base and efficiency, although they do call it “Coh base” for a reason.

All athletes undergo the full Coh testing package, which determines who they are as cyclists, and based on that, we adjust the load, interval intensity structure, frequency of training, and overall volume.

In contrast, road racers receive programs that incorporate longer endurance rides, tactical training, and environmental conditioning to prepare for varying terrains and weather conditions encountered outdoors. The technical side plays a massive part outdoors, as if you can´t descend quickly on your own, especially in poor weather, there is a very small chance you will do so in a group.

The interval structure for outdoor work varies as a “superstructure” isn’t feasible, so we need to simplify the workout structure without diminishing quality. This is always easier said than done.

What is your take on the importance of volume versus intensity for esports riders, and do you think this differs from road racing? How do you go about determining the appropriate balance of volume and intensity for an athlete?

In esports, intensity often takes precedence over volume due to the shorter, more explosive nature of races. However, a foundational level of true endurance and durability is still essential. For road racing, a balance of volume and intensity is crucial to build stamina, aerobic efficiency, and develop versatility.

Also, if you are not the top-level rider, you need to make yourself useful in many areas so your contract is extended and you have a job the following season. That being said, there is no one-size-fits-all approach—each athlete requires a different balance depending on their physiology, experience, and racing demands.

For some, traditional high-volume models such as 75-25, 80-20, or even 90-10 (where the majority of training is lower intensity with a smaller percentage of high-intensity work) still prove highly effective. These athletes respond well to extensive aerobic conditioning and can sustain high performance using well-established endurance training methodologies.

For others, I’ve developed new methods that challenge conventional models, incorporating multi-zone pairing within individual workouts and high lactate tolerance training. These approaches emphasize targeting multiple physiological systems within a session, rather than separating intensity and endurance into distinct blocks.

The recoveries, or lack thereof, are also shocking. In esports, where races demand repeated high-intensity surges with minimal recovery, this style of training can be particularly beneficial, allowing riders to build both explosive power and the ability to sustain it repeatedly under fatigue.

It certainly appears that more esports riders are turning towards non-traditional techniques, e.g., standing and/or low cadence (AKA, running on the bike). Do you think these techniques may be more optimal for indoor riding and have something to do with the impressive numbers we are seeing produced by esports athletes?

The rise of nontraditional techniques like standing efforts, low-cadence grinding, and “running on the bike” in esports isn’t just a trend—it’s a direct adaptation to the unique demands of virtual racing. Unlike outdoor riding, where aero positioning, road conditions, and bike handling play a major role, esports is purely about raw power output and sustained effort efficiency.

The impressive numbers seen in esports cycling aren’t just about these techniques, though—they’re also the result of hyper-controlled environments, perfect pacing, incredible engines, and zero external disruption, such as wind, terrain, handling, and other variables.

Some of the best engines I’ve personally seen are currently in esports. You wouldn’t believe how many 80+ VO2 max verified in independent lab tests there are—and they’re winning. That makes me particularly happy because as you know, I calculate VO2 from their power outputs and repeatability, and then when I see the lab test match that, I am a happy man. There’s nothing I like seeing more than talent and hard work thriving together.

Do you think there are any key training practices or philosophies underlying the huge numbers produced by esports cyclists, or does this purely come down to the unique racing demands and environmental factors, such as shorter races and more controlled racing environments?

The huge numbers seen in cycling esports result from a combination of targeted training adaptations and the unique demands of virtual racing. It’s not just about talent—it’s about how riders train specifically for the environment and leverage the controlled conditions to optimize performance.

Esports racing demands repeated high-intensity surges, so training reflects this with high-powered intervals of various duration layered within endurance work. Riders develop high lactate tolerance, allowing them to sustain efforts that would traditionally lead to a blow-up in outdoor racing.

Some follow a multi-zone pairing approach, combining threshold, VO2 max, and anaerobic work within the same session rather than isolating zones. Most stick to their usual routines, which is a mistake. Specificity is key for success.

The unique physics of indoor racing further amplify performance. Outdoors, power efficiency is affected by air resistance, road conditions, and tactical drafting, while indoors, every watt translates directly to speed. Perfect pacing, controlled cooling, and a fully optimized fueling strategy mean riders can execute at peak efficiency without external disruptions. Fixed CDA. Without the tactile feedback of road racing (bike handling, cornering, braking), all focus is on output, effort, and mental tolerance, changing how riders distribute their energy.

Esports racing rewards specific training adaptations in ways that road cycling doesn’t, and the numbers reflect that. The structured training approach—blended intensity, high-lactate tolerance work, low cadence, and targeted race simulations—is essential, but the controlled racing environment further amplifies performance. The combination of training evolution and optimized racing conditions is what drives the huge numbers we’re seeing and the aforementioned massive engines.

Key Takeaways

- Esports demands emphasis on high-intensity intervals with short recoveries to build maximal aerobic and anaerobic capacities and neuromuscular efficiency. It also requires the ability to recover quickly from these efforts, as is required for racing.

- Given the shorter duration of races and their ability to rely on carbohydrate stores, esports athletes have reduced requirements for endurance/fatigue resistance work; hence, most do less overall training volume.

- Reduced overall training volume means that esports athletes have greater time off the bike or in lower zones to recover. Therefore, they can handle the super intense workouts, which facilitate the adaptations required for racing.

- Multi-zone workouts (i.e., combining threshold, VO2 max and anaerobic work within the same session) are utilized as an efficient way of training multiple zones simultaneously and building fatigue resistance, while mimicking the demands of racing. In other cycling disciplines (i.e., road) zones are more often trained in isolation given the demands of races and practicalities of changing gears, finding suitable terrain, and keeping high intensity work relatively measured, in favour of a higher training volume to support the demands of racing.

Final Musings

Esports cycling is a distinct discipline that demands sustained high power over relatively short durations, typically less than 90 minutes. To meet these demands, emerging training methodologies focus on lower volume, higher intensity plans and multi-zone workouts. These approaches target the specific adaptations needed for success in virtual racing—huge anaerobic and aerobic capacities, exceptional neuromuscular efficiency, and a high tolerance for lactate buildup.

The results speak for themselves. Many elite esports cyclists produce power numbers that rival, and in some cases exceed, those of WorldTour professionals. It could also be argued that esports racing naturally selects athletes with standout physiological traits, such as high VO2 max and superior lactate tolerance—riders who may have seen limited success outdoors due to the added skill and tactical demands of road racing.

But genetics only tells part of the story. The evolution of esports-specific training has reset the performance benchmarks in this discipline. Combined with optimized environmental conditions and shorter, more intense race durations, these training methods are helping athletes reach new heights, particularly for repeated high-intensity efforts with minimal recovery.

References

Rivera-Kofler, T., Varela-Sanz. A., Cabo-Padron. A., Giraldez-Garcia. M., & Munox-Perez, I. (2024). Effects of Polarized Training vs Other Training Intensity Distribution Models on Physiological Variables and Endurance Performance in Different Level Endurance Athletes: A Scoping Review. Journal of Strength and Conditioning, 1-13.

Stöggl, T. L., and Sperlich, B. 2015. The training intensity distribution among well-trained and elite endurance athletes. Front. Physiol. 6:295. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00295

Seiler, S., & Kjerland, G. Ø. (2006). The impact of training intensity distribution on performance in endurance athletes. Sports Medicine, 36(3), 209-221.

Gallo, G. (2015). Intensity Distribution in Top 3 Giro D’Italia Finishers. Knowledge is Watt.

Semi-retired after more than 20 years as the owner and director of a private Orthopedic Physical Therapy practice, Chris now enjoys the freedom to dedicate himself to his passions—virtual cycling and writing.

Driven to give back to the sport that has enriched his life with countless experiences and relationships, he founded a non-profit organization, TheDIRTDadFund. In the summer of 2022, he rode 3,900 miles from San Francisco to his “Gain Cave” on Long Island, New York, raising support for his charity.

His passion for cycling shines through in his writing, which has been featured in prominent publications like Cycling Weekly, Cycling News, road.cc, Zwift Insider, Endurance.biz, and Bicycling. In 2024, he was on-site in Abu Dhabi, covering the first live, in-person UCI Cycling Esports World Championship.

His contributions to cycling esports have not gone unnoticed, with his work cited in multiple research papers exploring this evolving discipline. He sits alongside esteemed esports scientists as a member of the Virtual Sports Research Network and contributes to groundbreaking research exploring the new frontier of virtual physical sport. Chris co-hosts The Virtual Velo Podcast, too.

Kate is an elite racer for Esports team BL13 p/b Level Velo. In 2024, she won the Australian National Esports Championship and placed 24th at the Esports Cycling World Championships. She holds a Bachelor of Psychological Science and a Master’s in Speech Pathology from the University of Tasmania and works as a clinical speech pathologist. An avid reader and writer, Kate enjoys sharing insights into cycling esports and crafting thoughtful stories about the sport.